Ozzy Osbourne, just a guy who likes to make people smile

By Fred Varcoe

“I’m not the Antichrist, I’m not the Iron Man, I’m not the kind of person you really think I am . . . I try to entertain you the best I can, I wish I’d walked before I ran,” Ozzy Osbourne sings in “Gets Me Through,” the opening track on his new album, “Down to Earth.” It is at once a touching thank-you to his hordes of faithful fans and a dismissive fuck-you to those who have tried to condemn him or who have misrepresented him.

“It amazes me that people see me like this,” the Englishman complained in a weekend phone interview from his home in Beverly Hills. “I don’t go out very often; I watch TV a lot and stay home, so how do they know I worship the fucking devil or whatever? They don’t see me swinging off the rafters off my house or anything.”

Of course, any man who is prepared to bite the heads off live doves (in a meeting of CBS record executives) and bats (on stage) is hardly likely to get a fair shake when it comes to images in the media. “I thought it was a rubber bat,” Ozzy once said, somewhat disingenuously.

Other manifestations of his past drink and drug excesses didn’t help either. After polishing off four bottles of vodka one afternoon in September 1989, Ozzy told his wife, Sharon, “We’ve decided that you’ve got to go.” He then proceeded to strangle her. She managed to hit the security button in their home and the police got there before Ozzy could do any more damage to her – or himself.

He was charged with attempted murder, but after a drying out spell and an enforced separation from his family for three months, the couple got back together and stayed together. They’ve now been together nearly 20 years and Ozzy’s past indulgences – at least the drugs and drink part – have given way to exercise, a healthy diet and a family-centered life.

The MTV man

MTV will be offering an inside look at the Osbournes – Ozzy, Sharon, daughters Kelly and Aimee and son Jack – in a 13-part, fly-on-the-wall documentary series to be broadcast in the United States. Anyone who saw the precursor to the series a few years back, when Ozzy also allowed TV cameras into his home, will recognize that the king of heavy metal is anything but the monster he’s sometimes made out to be.

That’s not to say, though, that life chez Oz resembles “The Waltons.” The original documentary was more like “Absolutely Fabulous,” with Ozzy his usual cartoon self – a wealthy, foul-mouthed, heavily tattooed, uncompromising vision of horror for Middle America – and the kids on hand to keep the household from going out of control.

Picture this: Sharon has hired a chef to make breakfast for Ozzy. Eggs Benedict is not even in Ozzy’s vocabulary, let alone on his list of potential breakfast items.

“Why do we need a fucking chef to cook me breakfast?” he complains. “All I want is fucking eggs and bacon. We don’t need a fucking chef to do that.” Or words to that effect.

“Don’t swear, Daddy,” the kids tell him.

No one who has seen these images of Ozzy will mistake him for an accountant; they may, however, be confused by the sight of Ozzy under the thumb of his wife (who, as his manager and the daughter of legendary British promoter Don Arden, carries her own fearsome reputation) and children, not to mention the infamous photos from the past, of the out-of-control, drugged-up, boozing rock animal who kills wildlife on stage. The images just don’t seem to go together.

So who – or what – is the real Ozzy?

“It’s somewhere in between,” Ozzy admits. “I’m not a Satanist; I’m just a guy who likes to make people smile. Rock ‘n’ roll is the best thing that’s ever happened to me in my life because I can let people have fun.”

And the cartoon monster image?

“Well, it’s better than being a terrorist, isn’t it?” he suggests.

Ozzy hopes the MTV series is going to be shown in Japan.

“It would be really interesting to see a translation of what I’m saying and having me dubbed in Japanese,” he said. He would certainly prefer that to hearing himself in English.

“I cringe when I hear myself talking normally,” he says. “I hate the sound of my speaking voice. I sound like a mutant.” (Ozzy’s slurred Birmingham drawl prompted one American journalist to ask if the MTV series would be subtitled so people could understand what he’s saying – at which point, Sharon reportedly shouted: “Who said that?! . . . Stand up, you arsehole!”).

‘Japan’s been good to me’

If not on television, Japanese fans will have a chance to see the new lean and healthy Ozzy in the coming weeks when he tours Japan in support of “Down to Earth.” They can also be content in the knowledge that he’s likely to be recording his upcoming concert at the Budokan for a live album.

“I haven’t been there for a while, but the Japanese have always been good to me,” Ozzy says. “I’ve got a good fan base over there. I like the Japanese people, and I’ve always had a good time there.”

Though his bad-man image has proven appealing to teens all over the world, the reality is that he can only sustain his success as long as he is still producing the goods on record. And even at the age of 53, he is still producing awesome – and contemporary – rock ‘n’ roll. He admits that he’s able to do this with a little help from his friends.

“I work with teams,” he explains. “On ‘Dreamer’ [track 3 on ‘Down to Earth’], I worked with Mick Jones from Foreigner and Marty Freed. The melody line just came from nowhere. I’m not usually a melody maker, but ‘Dreamer’ is the coolest melody I’ve ever written.” In fact, it’s probably the closest he’s come to writing pure pop, which may not please all his fans.

Ironically, Ozzy supposedly left Black Sabbath in 1978 – when it was one of the biggest acts in the world – because he was unwilling to follow guitarist Tony Iommi into a more melodic strain of heavy metal. Since then, Ozzy the solo artist – still one of the biggest rock acts in the world (he’s sold over 40 million albums to date) – has been able to indulge in his love for The Beatles (“When I first heard ‘She Loves You,’ I couldn’t fucking believe it. They got me interested in music.”) and has come up with some of his own sweet melodies.

Of course, Ozzy’s bread and butter is still very much on the dark side. On “Down to Earth,” longtime sidekick Zakk Wylde cranks out monstrous guitar riffs that perfectly complement the air of menace and scary lyrics that are Ozzy’s trademark.

Despite the “Sabbath” reunion album, which he did a couple of years back with the original members of Black Sabbath (“It’s like visiting your relatives,” he says of their relationship), Ozzy’s got too much to look forward to to spend his time looking back. And while he was shocked over the recent death of George Harrison, he doesn’t lose any sleep thinking about his own demise.

A man alive

“It’s just one of those things that happens to all of us,” he says matter-of-factly. “I don’t think, ‘I’m dying, I’m dying, I’m dying’ all day, because while I’m thinking about dying, then I’m not living.”

Ozzy is still very much alive and is working like a madman: Besides the MTV series and the upcoming Far East tour, he and his wife also organize the Ozzfest, a heavy metal festival that tours mainly America and Europe. (“Jack chooses most of the bands now,” Ozzy admits.)

“We’ve been trying to take the Ozzfest to Japan, but the problem is the logistics are just ridiculous – the costs outweigh the profits,” Ozzy explains. “With all the equipment, the stage and the bands, it’s just too huge to do.”

With all these projects going, how long can Ozzy keep it up?

“I was asked if I would still be doing this at 35; I said yeah. At 45? Yeah. At 55? Well, I’m 53 now, so yeah. And at 65? Well, maybe, yeah – unless the plane goes down on Tuesday,” Ozzy jokes, adding: “There’s no rule saying you can’t rock ‘n’ roll at 60.

“If there’s an audience out there and they want to hear me, then it’s OK. If my fans fall by the wayside, if I’m playing to 25 people in The Whiskey on Sunset and I’m not enjoying it any more, then I won’t do it anymore.

“But I’m 53 and I’m still going. I’m the luckiest guy in the world and people still want to hear me, so it’s great.”

Stomu Yamash’ta and the sound of Zen

By Fred Varcoe

Stomu Yamashi’ta progressed from being a teenage musical prodigy in the 1960s to arguably the most famous Japanese person on the planet a decade later. Then he gave it all up and went to meditate in a Kyoto monastery for three years. For three decades, the musician that Time magazine once referred to as “the man who has changed the image of percussion” has largely stayed in Kyoto refining his art, refining his life and living in a Zen-like world of sounds and music.

This is not rock ’n’ roll. There’s no record deal, no tour, no merchandise, no groupies. There’s no timeline. Yamash’ta is a point in infinity, a musical shaman, a giver and receiver of life and music.

His most recent tangible product is a double DVD, “Walking on Sound,” in which he collaborates with Icelandic counter-tenor Sverrir Gudjonsson and which is referred to as a “Zen and Viking opera.” The first part is “The Void,” which brings together Yamash’ta’s percussion, Gudjonsson’s singing and vocalising, Syrian soprano Noma, the Irish flute of Dominique Bertrand, the shakuhachi of Genzan Miyoshi and the chanting of four Buddhist monks. The second part is “The Sound of Zen,” largely consisting of Buddhist chants accompanied by Yamash’ta’s percussion, Miyoshi’s shakuhachi and the yokobue of Michiko Akao. Both are live performances recorded at the Saint-Eustache Church in Paris. The other DVD is a documentary of how the performance came together.

At a young age, Yamash’ta’s reputation was established so rapidly that he was in demand the world over from the greatest musicians of his age. His entrée was classical music – he played as a guest with the Kyoto and Osaka Philharmonic Orchestras at the age of 14 – but his musical mind quickly absorbed everything around it, be it jazz, avant garde, rock or the abstract. He defined the role of the solo percussionist and started to improvise and compose, contributing to the soundtracks of movies such as “The Tale of Zatoichi,” “The Man Who Fell to Earth” and “The Devils.” He moved through avant garde to jazz before establishing the Red Buddha Theatre Company to showcase his idea of sounds and vision.

His most visible work in the rock world came in 1976 when he collaborated on the Go project with huge stars such as Steve Winwood (Traffic), Phil Manzanera (Roxy Music), Mike Shrieve (Santana), Klaus Schulze (Can) and Al Di Meola (Return to Forever). Yamash’ta had transformed himself from a classical teenage prodigy into a global rock star.

Giving it all up

Then he gave it all up, returned to Kyoto and stayed at a monastery for three years.

“I came back from Europe when I was at my peak, and many people wondered why I quit and came back to a Buddhist temple, suspending – almost giving up – my career,” Yamash’ta recalls. “I thought I should give up to become zero again, to get hungry again.

“I had to be honest to myself, what I felt. I was too lucky to be able to taste the best of everything, including classical music, contemporary music, jazz-rock fusion. I was able to collaborate with the best. This was a kind of fate and after tasting this kind of pure fate, I had to go back to something totally different, which you could call ‘religion,’ although I don’t like to use that word because it creates misunderstandings. I was glad because I had this almost desperate hunger which made me go to the temple. My father was associated with one of the most famous temples in Kyoto – Toji – and by this luck I found something that I had never experienced in my lifetime before. So it was a really good approach for me.”

In short, Yamash’ta wanted out of the “system.”

“When you become part of a system, at some point we need to make a transition to go to a different level,” Yamash’ta explains. “In today’s reality, we are facing this kind of transition.”

Zen uses meditation as the means to enlightenment and Yamash’ta took a similar path in the temple, which he refers to as “a spiritual environment of humility and innocence.”

“It gave me enormous joy and some kind of answer,” he says. “Suddenly, I could see myself very clearly.”

As if by fate, he learned of a stone with amazing sonic properties that was found in the mountains of Kagawa Prefecture on Shikoku Island.

“When I met the Sanukite stones, I felt like my life was almost complete,” he says. “Speaking personally, I got my answer to life so I feel I can end it, to depart to a different world. But of course, I am still living here, existing, and the last 25 or 30 years were for me more personal. And this personal thing was wonderful – to be able to spend this time as an artist. I didn’t have to concern myself with social benefit.”

But Yamash’ta doesn’t reject society. Far from it. He is more outgoing than some might think. He may think a lot and meditate a lot, but he laughs a lot and enjoys good company. It’s easy to see that talking – communicating – puts a sparkle in his eye.

“Now, I feel like maybe I’m at my final stage, so from now it’s more like my mission – or whatever I can do – to communicate, to make some kind of function to create a better beauty, and this beauty can lead to a new ‘garden,’ ” he says.

The life and sounds of stone

His musical endeavours over the last quarter of a century have revolved around bringing the Sanukite stones to life. Anyone can bang a drum, but breathing life into inanimate objects takes a belief that the objects really do possess life and power. Yamash’ta caresses his stones and communicates with his stones as if they are alive. For him, they are. They possess life – in their unique sounds and their 20-million-year history. Yamash’ta the percussionist is not a member of a band or orchestra; he does not beat time to someone else’s rhythm. He does not beat time, period. He is a channeler of sounds. He discovers the sounds of the stones. They are not his sounds; they are the stones’ sounds.

“The Void” is a journey through history, through life, and a message of peace and hope for the future. Yamash’ta worries about the younger generation and wishes they could find the awakening that he has experienced over the last three decades.

“Compared to our age, young people have a more established education,” he explains. “They have more information, but being young, the tragedy is they have not had enough experiences that could create a new dimension, and to face a new consciousness; you need knowledge to overcome. You have to filter knowledge through experience. And maybe this is one reason why young people are becoming so inward-looking today.

“I was glad about Steve Jobs’ message: ‘Stay hungry, stay foolish.’ That is very Zen. To understand foolishness is a very, very deep message. I think in the ’60s and ’70s we had a very good kind of foolishness and this opened a new door, a desire to taste humanity. When you hear some of today’s songs, it’s so obvious they have not had good experience. I’m sorry to say they are just singing social information. If they allowed themselves to be more ‘foolish,’ they could find a better approach to create a new artistic scene with coexistence.”

Yamash’ta is no fool, but he has the spirit of a fool – the fool of Shakespearean literature, a fool that has more wisdom than those around him, but which is not always obvious. As in meditation, sometimes you have to close your eyes to see the light.

Metallica live at Yoyogi Pool, Tokyo, 13 May, 1989

Metallica: ’80s punk metal the primeval way

By FRED VARCOE

Maybe the Ayatollah was right; perhaps the creators of artistic creations that are blasphemous should be strung up.

Metallica’s recent performance in Tokyo brought this issue to mind, but they saved their necks by producing absolutely, nothing that could be interpreted as an artistic creation.

Not since Motorhead has heavy metal endured such affrontery.

But whereas Motorhead, the progenitors of speed metal, became palatable and remained unsuccessful by playing to their strengths, Metallica have become hugely successful and obscenely unmusical by concentrating on their deficiencies.

To their credit, Metallica have made it on their own terms. In an interview with Musician magazine, drummer Lars Ulrich admitted, “This is not rock ‘n’ roll for the people; this is rock ‘n’ roll for ourselves. We do what satisfies us.”

At first, both the public and the media were slow to pick up on the band. Indeed, they have achieved their success in the face of either negative reaction or no reaction at all. Radio stations avoided them like the plague.

But the band won through and their ” … And Justice For All” album has racked up sales of 1 million in the United States, which just goes to show how many sick people there are in the world.

With, the success of “Justice,” the media have been crawling over the band like maggots. Take this, from Musician magazine: “Metallica’s evolved from a troupe of good-natured thrash louts … to a platinum-selling band in the process of bringing heavy metal out of the Dark Ages” (straight into the Stone Age?).

And according to the U.K. magazine Sounds, “Metallica are the definitive metal band of the ’80s.”

A depressing thought, but in many ways Metallica do represent the ’80s – culturally, not musically. Last week, of course, Guns N’ Roses were the band of the ’80s. Axl Rose and the boys certainly play good old rock ‘n’ roll, but the emphasis is on the old.

Like Metallica, Rose is a child of the ’80s living off the music of the ’70s.

Both Guns N’ Roses and Metallica feed off aggression. But whereas the former channels it into the ’80s version of blues-based hard rock, Metallica take the more primeval approach and end up as the ’80s version of punk metal.

And their appeal seems to lie in their aggression. You don’t need brains to appreciate their music; in fact, not having brains is a prerequisite to appreciating their act.

Their music is based on power-chord riffs and … er … that’s it.

Perhaps I’m forgetting the vocals (at least that’s what I’ve been trying to do). Rhythm guitarist/vocalist James Hetfield doesn’t sing, he growls in as doom-laden a fashion as he can muster. And the vocals don’t have even the remotest sign that they’ve been thought out. Hetfield smashes out the riffs and then does a grunt over, as we say in the music world.

But it’s the riffs that get you, Musician magazine’s grovelling writer describes Hetfield’s playing as “weird cadences and lurching phrases, the strange stops, starts and sideways mid-verse leaps into new time signatures that make Metallica sound like Godzilla weaving through Tokyo on a drunken jag.”

And when Godzilla returned home last week, he got an astonishing response. Even the guy who told the audience at Yoyogi’s Olympic Pool that they were going to have a good time (otherwise they wouldn’t have known) got a bigger cheer than most bands get in Tokyo.

Metallica is America’s ultimate greaser’s band (Motorhead still holds the title in the U.K.). Hetfield and bassist Jason Newstead seem to play their instruments with their hair, but if you listen closely it sounds more like they play them with a lead pipe. In Newstead’s solo, only a visual check tells you that his left hand is moving.

The first five numbers were only identifiable as five numbers by the pauses in between. The riffs, the vocals, the lead come together like a freeway pileup, a collision of sounds entirely unrelated and musically meaningless.

“Master of Puppets,” “One” and “Seek & Destroy” all had the quality of construction even if what was constructed didn’t have quality. “Master” is heavy-metal minimalism with barely distinguishable vocals, and “One” has a sense of drama even if it doesn’t have a sense of music. “Seek & Destroy” is good because they lifted the riff from “I’m A Man.”

Two numbers that were listenable were “Last Caress,” which showed the band’s punk influence, and “Breadfan” by legendary Welsh rockers Budgie. But in reality, Metallica is where the wall of sound meets the wall of death.

At Yoyogi last week, death won.

Drummer Lars Ulrich has some useful advice: “If you like it, come along. If you don’t, stay the f*** away.”

Don’t worry, Lars, I’m one step ahead of you.

(Originally published in The Japan Times)

Sinawe

Korean rocker carries on the family business

By Fred Varcoe

Go to Korea and you feel like everyone’s got a chip on their shoulder. It’s like everyone wants to pick a fight with you. On this occasion, someone did.

I was just sitting at the bar drinking with Korea’s most famous rock band, Sinawe, and a few friends when this young salaryman started pointing in our direction and mumbling something about the “girl-like” longhairs in the bar. But like my friends, I tried to ignore him.

When he got up, I ignored him a little less, and when he knocked the barmaid flying into a glass table with a drunken lurch, I thought, “That’s . . .” I didn’t have time to think much more as the four members from Sinawe leapt on the guy, smashed their fists into his face, kicked him in the guts and finished him off by bringing a couple of chairs down on his head. Then we ordered another round of beers and resumed our conversation on whether or not Pearl Jam was mainstream or alternative.

If anyone in Korea has a right to be angry, Sinawe guitarist and leader Shin Dae Chul is well-qualified. At the age of 10, his life was turned upside down when his father, Shin Chung Hyan, was busted for drugs and sent to jail.

“When my father got busted, I felt betrayed by society,” the younger Shin said. “Even at the age of 10, I couldn’t believe people got put away just for smoking dope. Almost all the musicians around at the time smoked, but my father was the only one they crucified.

“It still bugs me.”

Just as Shin Chung Hyan was no ordinary musician, it was no ordinary bust. Shin Sr. was the very foundation of South Korean rock ‘n’ roll. But more than that, he was an integral part of the troubled social and political landscape in South Korea in the ’60s and ’70s.

After paying his dues playing for U.S. servicemen on military bases in Seoul, he went on to become South Korea’s top guitarist, composer and producer. Such was his popularity that President Park Chung Hee asked him to write a song for Korea. (“No deal” was the reply. Top marks for integrity, perhaps, but zip for political astuteness.)

In the late ’60s, Shin wanted to try and understand what was happening in the West. “I invited a lot of foreign hippies to my house after a concert in 1968,” he explained. “They smoked a lot of dope. I wanted to understand Jimi Hendrix — his music, his feelings, his image and his mood.” So Shin tuned in, turned on and dropped out.

“I woke up about a year later and got back to work,” he continued. “A few years later, some Korean musicians came to my house and were interested in finding out about marijuana. I didn’t really smoke any more, but I had a plant in the house and gave it to them.”

Bad move. One of them was an associate of President Park’s son, Park Chi Man. Eventually word got back to daddy and the defecation hit the oscillator.

A lot of musicians were arrested, but Shin took the rap and got thrown in jail for four months. At the time, Park was on the verge of a political crisis and since rock ‘n’ roll was a medium for unrest, it had to go. Shin’s music was banned completely in South Korea and when he came out of jail, he was basically a nonperson, shunned by his countrymen and divorced from his profession.

For five long years, Shin endured the pain of ostracism. Then, in October 1979, Park was assassinated. For Shin, down on his luck and running out of sanity, it was his moment of retribution, although he doesn’t look back in anger.

Although he never quite attained the musical heights he had reached previously, Shin’s exile did have one positive result — he could spend more time with his family.

Dae Chul learned well from his father and like a good Korean eldest son, he took over the family business. As his father was the prime mover in the first wave of Korean rock, so Shin Jr. became the prime mover in the second wave.

In 1986, when he was just out of high school, his band, Sinawe, released its first album. In a land dominated by disco in the first half of the ’80s, Sinawe’s brooding, if rough-edged, metal ripped across the musical landscape. It sold 400,000 copies and spawned a host of imitators. At 18, Shin Jr. became the focus of South Korea’s rock scene.

Although rock has been overtaken by dance music in the popularity stakes, Sinawe and Shin Dae Chul continue to maintain their position as prime movers in the heavier side of the Korean music scene.

That can be seen in some of Shin’s lyrics. Thirteen years on from his debut album, Shin has abandoned the rather predictable ’80s metal of his formative years and is now exploring the grungier, darker side of life and music.

The gravel-edged vocals blend in with a meaty rhythm section and Shin’s dominant guitar, the music reflecting the gloom that seems part of the Korean national psyche.

Shin himself leads the band from a position of strength. He handles most of the music and most of the business.

With his latest album, “Psychedelos,” Shin has taken a step back from the Kurt Cobain-like primitiveness of his previous two albums and tried to blend a few more melodies in with the mayhem. There’s no less power, but it’s less abrasive.

After jamming with Sheena and the Rockets a few months ago, Shin has now opted to bring the whole band over for a couple of live dates in Tokyo. More than a few curious Japanese rock stars are expected to turn up to see what the Koreans already know: Whether he’s swinging a chair or an ax, Shin Dae Chul will knock you out.

(Originally published in The Japan Times)

Motorhead at Nakano Sun Plaza, June 10, 1991

Volcano rock blasts crowd at Sun Plaza

By Fred Varcoe

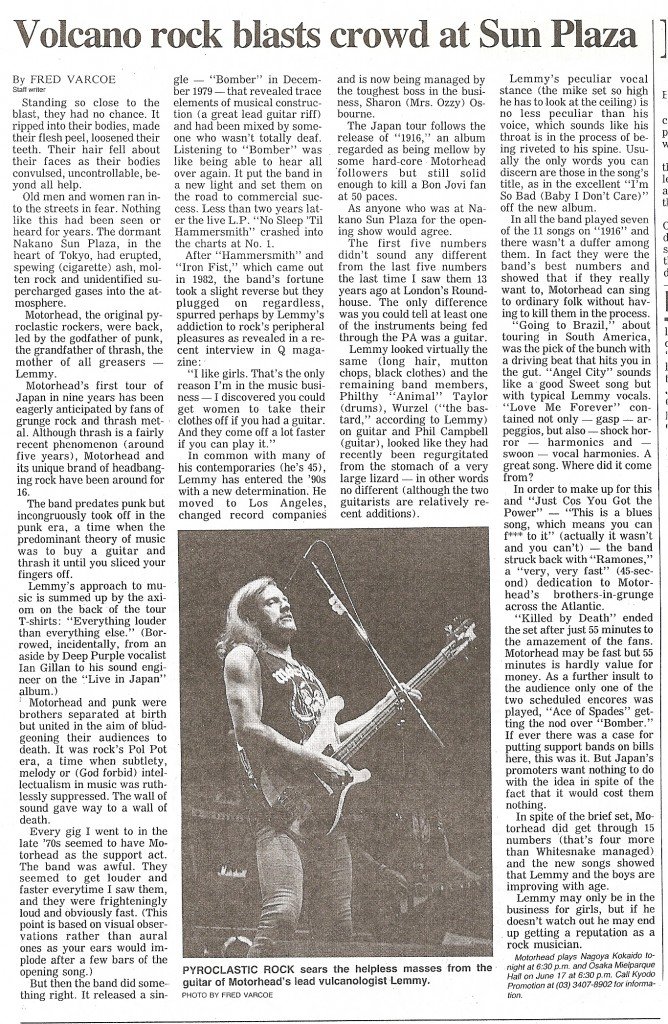

Standing so close to the blast, they had no chance. It ripped into their bodies, made their flesh peel, loosened their teeth. Their hair fell about their faces as their bodies convulsed, uncontrollable, beyond all help.

Old men and women ran into the streets in fear. Nothing like this had been seen or heard for years. The dormant Nakano Sun Plaza, in the heart of Tokyo, had erupted, spewing (cigarette) ash, molten rock and unidentified supercharged gases into the atmosphere.

Motorhead, the original pyroclastic rockers, were back, led by the godfather of punk, the grandfather of thrash, the mother of all greasers: Lemmy.

Motorhead’s first tour of Japan in nine years has been eagerly anticipated by fans of grunge rock and thrash metal. Although thrash is a fairly recent phenomenon (around five years), Motorhead and its unique brand of headbanging rock have been around for 16.

The band predates punk but incongruously took off in the punk era, a time when the predominant theory of music was to buy a guitar and thrash it until you sliced your fingers off.

Lemmy’s approach to music is summed up by the axiom on the back of the tour T-shirts: “Everything louder than everything else.” (Borrowed, incidentally, from an aside by Deep Purple vocalist Ian Gillan to his sound engineer on the “Live in Japan” album.)

Motorhead and punk were brothers separated at birth but united in the aim of bludgeoning their audiences to death. It was rock’s Pol Pot era, a time when subtlety, melody or (God forbid) intellectualism in music was ruthlessly suppressed. The wall of sound gave way to a wall of death.

Every gig I went to in the late ’70s seemed to have Motorhead as the support act. The band were awful. They seemed to get louder and faster every time I saw them, and they were frighteningly loud and obviously fast. (This point is based on visual observations rather than aural ones as your ears would implode after a few bars of the opening song.)

But then the band did something right. It released a single – “Bomber” in December 1979 – that revealed trace elements of musical construction (a great lead guitar riff) and had been mixed by someone who wasn’t totally deaf. Listening to “Bomber” was like being able to hear all over again. It put the band in a new light and set them on the road to commercial success. Less than two years later the live L.P. “No Sleep ‘Til Hammersmith” crashed into the charts at No. l.

After “Hammersmith” and “Iron Fist,” which came out in 1982, the band’s fortune took a slight reverse but they plugged on regardless, spurred perhaps by Lemmy’s addiction to rock’s peripheral pleasures as revealed in a recent interview in Q magazine:

“I like girls. That’s the only reason I’m in the music business – I discovered you could get women to take their clothes off if you had a guitar. And they come off a lot faster if you can play it.”

In common with many of his contemporaries (he’s 45), Lemmy has entered the ’90s with a new determination. He moved to Los Angeles, changed record companies and is now being managed by the toughest boss in the business, Sharon (Mrs. Ozzy) Osbourne.

The Japan tour follows the release of “1916,” an album regarded as being mellow by some hardcore Motorhead followers but still solid enough to kill a Bon Jovi fan at 50 paces.

As anyone who was at Nakano Sun Plaza for the opening show would agree.

The first five numbers didn’t sound any different from the last five numbers the last time I saw them 13 years ago at London’s Roundhouse. The only difference was you could tell at least one of the instruments being fed through the PA was a guitar.

Lemmy looked virtually the same (long hair, mutton chops, black clothes) and the remaining band members, Philthy “Animal” Taylor (drums), Wurzel (“the bastard,” according to Lemmy) on guitar and Phil Campbell (guitar), looked like they had recently been regurgitated from the stomach of a very large lizard – in other words no different (although the two guitarists are relatively recent additions).

Lemmy’s peculiar vocal stance (the mike set so high he has to look at the ceiling) is no less peculiar than his voice, which sounds like his throat is in the process of being riveted to his spine. Usually the only words you can discern are those in the song’s title, as in the excellent ”I’m So Bad (Baby I Don’t Care)” off the new album.

In all, the band played seven of the 11 songs on “1916” and there wasn’t a duffer among them. In fact they were the band’s best numbers and showed that if they really want to, Motorhead can sing to ordinary folk without having to kill them in the process.

“Going to Brazil,” about touring in South America, was the pick of the bunch with a driving beat that hits you in the gut. “Angel City” sounds like a good Sweet song but with typical Lemmy vocals. “Love Me Forever” contained not only – gasp – arpeggios, but also – shock horror – harmonics and – swoon – vocal harmonies. A great song. Where did it come from?

In order to make up for this and “Just Cos You Got the Power” – “This is a blues song, which means you can fuck to it” (actually it wasn’t and you can’t) – the band struck back with “Ramones,” a “very, very fast” (45-second) dedication to Motorhead’s brothers-in-grunge across the Atlantic.

“Killed by Death” ended the set after just 55 minutes to the amazement of the fans. Motorhead may be fast but 55 minutes is hardly value for money. As a further insult to the audience only one of the two scheduled encores was played, “Ace of Spades” getting the nod over “Bomber.” If ever there was a case for putting support bands on bills here, this was it. But Japan’s promoters want nothing to do with the idea in spite of the fact that it would cost them nothing.

In spite of the brief set, Motorhead did get through 15 numbers (that’s four more than Whitesnake managed) and the new songs showed that Lemmy and the boys are improving with age.

Lemmy may only be in the business for girls, but if he doesn’t watch out he may end up getting a reputation as a rock musician.

(Original published in The Japan Times)

Photos by Fred Varcoe

Paul McCartney live at the Tokyo Dome, 12 Nov. 1993

Politics cloud McCartney’s success

By FRED VARCOE

(Originally published in The Japan Times)

Paul McCartney may not be looking for absolution, but he’s going to get some anyway. At the Tokyo Dome last Friday, the first of five concerts in Japan, he proved that he still has the wherewithal to put on a decent show, but his desire to make a political statement threatened to overshadow the proceedings.

Many Beatles fans have given up on Paul, especially since John Lennon died. John no longer has the chance to sully his reputation and fans have largely forgotten his largely forgettable swansong “Double Fantasy.”

But Paul is still on the active list and as such is capable of recreating such bilge as “Put It There,” “When I’m 64” and “The Girl Is Mine,” which was also the nadir of Michael Jackson’s career. Mercifully, none of this was apparent at the Tokyo Dome. The only hint of danger was having wife Linda on stage behind a Union Jack and a banner reading “Go Veggie” – a curious way to address her husband.

Linda gave the impression of being seated behind a keyboard, but whatever it was, it remained hidden by a curious collection of toys and the aforementioned flags. No aural evidence of a keyboard struck one’s sensory organs and requests to McCartney’s staff for a tape of Linda’s contribution to the gig were turned down. I concede that she was the best tambourine and maraca player of the day, but her presence still smacks of nepotism to me. The biggest compliment I can pay Linda is that she appears to be well ahead of Yoko “Let’s Karaoke” Ono.

If the show was an overall plus, it started with a massive minus. As the fans entered the Dome, they were handed anti-vivisection leaflets, presumably at the instigation of the McCartneys. This was more or less confirmed by “Help – a Day in My Life,” a 10-minute video of Beatles songs and images from the ’60s.

At least, that’s how it began. As the fans took in the sound of the Fab Four and watched the screens surrounding the stage, everything seemed happy enough. But as the video neared its climax, the images changed to pictures of nice animals, and then we saw a bullfight, cows being roped in a rodeo, harpoons piercing whales, toxic waste being dumped in the sea, a Greenpeace inflatable under attack.

Then the pictures became more sinister, showing animals in labs undergoing cruel experiments and having various parts of their bodies ripped apart in the name of science. It was disgusting and, Paul and Linda, you have succeeded in converting one lost soul – I am never going to eat monkey meat again.

But the most sinister part about the video was the fact that Paul was using Beatles music to soften the blow. The whole thing was reminiscent of Alex’s treatment in the movie “A Clockwork Orange,” when he is drugged and shown violent films that make him throw up, so putting him off violence. Because the soundtrack contains the one beautiful thing that Alex can appreciate – classical music – the treatment effectively kills off any pleasure he derived from music as well as violence.

No one can deny Paul’s right to fight for a cause, but his fans go to see him for his music, not for his politics. Japanese fans, who never get an opening-band warmup despite paying the highest ticket prices in the world, have a right to have their precious leisure time unsullied by such liberties.

As for the concert itself, at least McCartney left most of his own material out of it. As in his 1990 world tour, he relied largely on Beatles numbers to carry the show, the difference being that this time around they had a bit of life to them.

That may augur well for Paul’s proposed reunion with George Harrison and Ringo Starr next year when the trio plan to produce some music for a Beatles documentary. It is not, according to McCartney spokesman Geoff Baker, intended to be an official Beatles reunion, but the trio will get together in the studio “and see what happens.”

Baker also confirmed that McCartney’s current “New World Tour” is not his final tour, contrary to rumours in the Japanese press.

Judging by the quality of the music in last week’s show this is a good thing. The whole show was a vast improvement over his last effort three years ago. Everything was much simpler. There were no gimmicks; the light show and set were spare (just a couple of explosions during “Live and Let Die”); and Paul laid off the patronizing patter (his previous attempts at simple English for the Japanese were far closer to simpleton’s English – this time round he spoke a bit of Japanese, but mercifully all communications were kept to a minimum).

Basically, Paul let his music do the talking for him and on that score he was a winner all the way. Having been together for some time now, the band showed the value of not messing around with a winning team. Guitarist Robbie McIntosh was nothing short of brilliant, providing some real feeling to numbers that had previously been numbed by overexposure and taking a load off McCartney at the same time.

But the biggest plus of the night was Paul himself. Paul has always been thought of more as a songwriter than anything else, but listen to any Beatles record and you will discover a truly stunning bass player and a closet Little Richard bursting out. After the band’s mediocre performance three years ago, there was little point in hoping to see anything new. But at the age of 51, Paul can still belt with the best of them, and on numbers such as “Let Me Roll It,” “Can’t Buy Me Love” and “Magical Mystery Tour,” he wasn’t holding anything back.

Paul’s vocals may have carried the tunes, but, of course, the tunes ain’t bad themselves. Starting off with “Drive My Car” and ending with “Hey Jude,” the set contained many of Paul’s highlights as a Beatle, including “Lady Madonna,” “Let It Be,” “Back in the USSR” and “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

The biggest surprise was how strong some of his softer stuff sounded. “Yesterday,” “Michelle” and “My Love” all sounded surprisingly fresh thanks to Paul’s fine vocals, and McIntosh’s funky guitar work transformed “Coming Up” from the realms of the also-rans to that of a soulful front-runner. Even the stuff off Paul’s new album, “Off the Ground,” was strong, especially the somewhat Beatlesque “C’mon People.”

The biggest disappointment was the absence of McCartney’s one solid classic as a solo artist, “Maybe I’m Amazed,” but “Live and Let Die,” with one of the great riffs of the ’70s, went some way to making up for it.

Paul may not be the most likeable ex-Beatle in the world, but as a live performer, he showed he still has the cojones to live up to his illustrious past.

Whether or not he has the cojones to lose his tambourine player is a different matter.

Manic Street Preachers

(Originally published in The Japan Times)

By Fred Varcoe

To some, the Manic Street Preachers are the new Sex Pistols, the new Guns N’ Roses, the new Nirvana, the British Guns N’ Roses, the British Nirvana, etc., etc.

You get the idea.

Whoever they are – and they will insist, no doubt, that they are merely the Manic Street Preachers – there always remains the danger that this week’s new wild boys could turn into New Punks On The Block.

One of the horrors of old age (35.96 years) is that you keep telling yourself, “That’s been done before.” Of course, my parents tried to say this, but lacked the conviction of actually knowing what had gone before. In fact, they were hoping that nothing like (insert horror of your particular generation here) had ever happened and merely thought that if I thought something wasn’t original I would lose interest in it.

In reality, of course, if what had gone before was so horrendous as to unsettle my parents, then I certainly wanted some of it as part of my antisocial weaponry. As a result, my parents were convinced in the ’70s that I was: 1) worshipping the Devil (Black Sabbath); 2) taking acid trips to Katmandu (Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd); and 3) killing off prominent members of the establishment (the Clash and Sex Pistols).

Little did they know that I was secretly conforming to their social values – well, I was closer than they thought – and that, far from worshipping the Devil, we were actually fairly good mates.

The Manic Street Preachers, like most bands, are doubtless not interested in comparisons to what’s gone before. Straight musical comparisons of the type “The Beatles are better than the Stones” or “The Jam is better than the Who” rarely do more than irritate musicians. Still, the past is an important point of reference and, as music is an evolutionary art, it has significance.

The band’s ironic allusion to the past in “Condemned to Rock ‘n’ Roll” makes the point that we’re talking about an indefinite now rather than a series of generational crises:

“The past is so beautiful

The future like a corpse in snow

I think it’s all the f—ing same

It’s a life sentence babe.”

The Preachers have been shot out of the same gun that produced the angry sounds and sneers of bands like the Clash and the Sex Pistols. (On Fuji TV’s “Beat U.K.” recently, lead singer/guitarist James Dean (groan) Bradfield tried to impress the viewers with a couple of “f— you’s” while bassist Nicky Wire did his best Sid Vicious impersonation and came across as being genuinely thick.)

Perhaps significantly, they too have risen to the fore in a deep economic recession. The bleak prospects facing the young and unemployed of Britain have given rise to a new breed of angry young musicians and, just as important, a new breed of angry young fans.

As punk was a welcome antidote to the disco dross of the ’70s, so the new breed of the ’90s is welcome relief from the neo-hippy dirges of the Manchester scene.

That the Manic Street Preachers arc the most exciting band to come out of Britain in recent years is hardly surprising. They are virtually the only exciting band to come out of Britain in recent years.

The band’s Japanese debut at Club Citta on May 11-13 was sold out weeks ago and could easily have stretched beyond a week. After Nirvana’s Japanese tour earlier this year, it was the most eagerly awaited rock event of 1992. But unlike Nirvana, the Preachers went some way to delivering live what they promised on their debut album, “Generation Terrorists.”

The main difference was balance. The songs on the album, while leaving no doubt we are dealing with anger, were presented with a slightly sugar-coated production job. Live, the energy level hits the high end of the scale as 1,000 sweaty Japanese punks and rockers bounce up and down to the Preachers’ very direct brand of rock ‘n’ roll.

Where Nirvana is slightly flakey and occasionally laid back in delivering the message and the music, the Preachers slam it into your face. The guitars of Bradfield and the slightly – okay, let’s be honest, very – redundant Richey James grind along like a rivet gun, laying down a foundation for Bradfield’s excellent and, unlike Johnny Rotten’s or Joe Strummer’s, controlled vocals.

If you can’t tell how angry Bradfield is just by looking at him (believe me, you can), you can take a peek at the lyrics that accompany the CD.

“Madonna drinks Coke and so you do too

Tastes real good not like a sweet poison should

Too much comfort to get decadent

Politics here’s death and God is safer sex” (“Slash and Burn”).

Or:

“Useless generation

Dumb flag scum

Repeat after me

F— Queen and country

Repeat after me

Imitation demi gods

Repeat after me

Dumb flag scum” (“Repeat (U.K.)”).

The Japanese fans may understand the album title, but probably don’t make much headway with the semi-literate lyrics. The important thing is the gist of the message gets across. With the concert being held in the all-standing human crush heat of Club Citta, there is an intensity there that is usually lacking at theater venues.

Added to which, the Preachers’ penchant for choral-style hooks allows the Japanese audience to actively participate and get closer to the band and the music. A few adventurous fans climb over the shoulders of the mob down front and threaten to get on stage, but always back out at the last minute, much to the disappointment of the fans and the band, who are hoping that the barrier between the two will break down. But this is Japan, so it won’t.

Still, as events in the metropolis go, it made its mark. The band has the same universal appeal as Guns N’ Roses and Nirvana, and, like the Seattle rockers, it has just taken the first big step. Fame and money are on their way. Providing Bradfield keeps his muse (with five more years of a Conservative government, this should be no problem), the future looks bright. Next time round, the Manic Street Preachers could be playing the Budokan.

Except there may not be a next time round if the band members are to be believed. They have said they will break up rather than outlive their usefulness. They don’t want to end up as memorial pieces.

A wise move. Otherwise we could be looking at a fate worse than death: the new Sham 69.

Gary Moore

Review of Gary Moore, originally written for The Japan Times

Concert shows more of Moore can only be better

Concert shows more of Moore can only be better

Guitarist Gary Moore’s blues-rock talent shines at Nakano Sun Plaza

By FRED VARCOE

Somebody’s judgment must be wrong.

Last year, Yngwie Malmsteen played the Budokan; last week Gary Moore played Nakano Sun Plaza. Malmsteen is a technically brilliant guitarist with all the musical feeling of a cardboard box and a face that girls would die for (and when they hear his music, they no doubt frequently do).

Moore, on the other hand, looks like he’s been visited by a particularly nasty biblical curse, but plays and sings as if touched by the hand of God.

Moore may be slightly less than megabig in Japan, but he is recognized in Europe as one of rock’s premier guitarists and as a strong singer and powerful songwriter.

But he took some time finding both success, in commercial terms, and a firm musical direction. He first emerged with Skid Row — no relation to the new U.S. band of the same name, which was unaware of the duplication — back in the early ’70s, before moving on to the heavy power-jazz of drummer Jon Hiseman’s band Coliseum II.

Moore gained wider fame when he joined fellow Irishman Phil Lynott in Thin Lizzy for a short spell in 1973 after the departure of Eric Bell and again in 1978, before being fired a little more than a year later for missing two gigs on a U.S. tour.

Nevertheless he formed a fruitful, if not productive, partnership with Lynott that resulted in Moore achieving chart success for the first time with “Parisienne Walkways,” from his patchy 1978 debut album “Back on the Streets.”

There is no doubt the partnership could have gone on to greater things, but Lynott finally overabused himself and croaked in 1986.

By then, Moore had half a dozen albums in the racks, a firm reputation as a guitarist and performer and enough strong songs to make up a strong set.

And a strong set is what he served up at Nakano Sun Plaza. Opening with the title track from his new album “After the War,” Moore comes across as aggressive, but as the crowd responds — the Sun Plaza does at least have the advantage of being intimate — a smile creases his already well-creased face.

Barely had the chunky riffs of “After the War” started to fade when Moore crunched into the old Yardbirds’ hit “Shapes of Things.” The original was powerful enough, but Moore’s version — even on the “Victims of the Future” album — is simply devastating. Riffs crash down all around, colored by slick overlays and a scorching lead with a creditable lead vocal from keyboard player/guitarist Neil Carter. As good a version of a hard-rock song as you’ll find.

But although Moore’s blues-rock virtuosity reeks of venom, he has a gentler side to his musical soul, and on the instrumental “So Far Away,” accompanied only by Neil Carter’s synthesizer, he showed the power of the sustained note as the Sun Plaza glowed to the sound of Moore’s Les Paul in a way that perhaps only Carlos Santana has ever equaled.

Another strong characteristic in Moore’s singing, playing and songwriting is his ability to blend Irish folk music influences into his naturally hard-edged style without ever compromising on power.

Indeed, the passion Moore derives from his homeland is evident on so many of his songs, and those musicians whose passion fires their music invariably have a head start over the likes of Yngwie Malmsteem and the cardboard box set.

On numbers such as “Blood of Emeralds” (“all about Ireland”) from the new album; the acoustic “Johnny Boy”; and the main set’s final number, “Over the Hills and Far Away,” with its beautiful, warm emotional hook, Moore fired up himself and his fans and demonstrated a degree of intensity sadly lacking in so much of today’s soulless hard rock.

Moore encored first with two rockers — “Rockin’ Every Night” and “All Messed Up” — before coming back for “Johnny Boy” and the divine “Parisienne Walkways” with his solos lit up by laser-intense sustain and lightning flashes of speed.

If quality determined the size of hall an artist played, then Gary Moore should be playing the Tokyo Dome and Yngwie Malmsteen should be playing the men’s room at Shibuya Station. Somebody’s judgment must be wrong, but it wasn’t that of the 2,000 or so people at Nakano Sun Plaza.

I guess it must be Yngwie’s.