By Fred Varcoe

Oh crap! We’ve got the Olympics.

Joy of joys. Hang out the bunting. Let’s have a street party. It’s a good thing, right?

“It is immoral to invite the Olympic Games to Japan where the health environment cannot be secured.” Well, the “loony” left would say that, wouldn’t they? But the “loony lefty” who said this, according to David McNeill’s report in The Independent, was former Japanese ambassador to Switzerland Mitsuhei Murata, who maintains that the situation at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is too unstable to allow a major event such at the Olympics to be held 250 km away.

“A dark cloud looms over Tokyo’s prospects due to an escalating crisis at a stricken nuclear power plant,” a report from Xinhua’s news agency stated before the bid. The joy of Tokyo’s success hasn’t blown the dark cloud away. “Faith in both TEPCO and the government’s ability to disseminate timely and accurate information to the global community, as well as their ability to effectively and definitively contain the crisis, is diminishing,” the report added. Nothing new there.

In the days following Tokyo’s successful bid to host the 2020 Olympic Games, media reports in Japan reminded the people there of the cost of the March 11, 2011, earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. Over 16,000 people died with more than 2,000 still missing, presumed dead. The dead won’t benefit from the Olympics, while the living are still struggling to benefit from the world’s generosity following the disaster.

Nearly 300,000 people in Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures are still living in temporary housing. Some have homes in irradiated areas that they can never return to. They need new homes (they need new lives). Maybe there’s a shortage of construction workers in Japan … There’s obviously not a shortage of money. According to the Asahi Shimbun, around $1 billion of disaster-relief money was spent on unrelated projects, including the counting of sea turtles on beaches. At this rate, the Olympic athletes will have accommodation before the disaster-affected homeless of Tohoku.

Mr. Abe’s alternative truth

Before the vote, the Fukushima crisis was seen as a potentially deciding factor for Tokyo’s bid. As media reports outlined a new crisis with the water tanks at Fukushima, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was despatched to the vote in Buenos Aires to allay the fears of those who might want to vote for Tokyo. But he wasn’t convincing everyone on the home front.

As McNeill wrote in The Independent: “Many have expressed concerns that a litany of crises faced by the Japanese government makes it entirely unsuitable to host such a global event. Experts have blamed Japan’s government and nuclear regulators for taking their eye off the Fukushima clean-up since Mr Abe returned to power late last year.”

Others went even further. Reiji Yoshida wrote in The Japan Times: “One question that emerged among the public immediately after Tokyo won the right to host the 2020 Olympics was whether Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made an incorrect statement, or told an outright lie, about the contaminated water issue at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant.

“During the Tokyo bid delegation’s final presentation before the International Olympic Committee in Buenos Aires on Saturday, Abe stressed that the ‘effects from the contaminated water have been perfectly blocked within the (artificial) bay’ of the wrecked nuclear complex, and said ‘the situation is under control.’ …

“Tokyo Electric Power Co. admitted that a lot of water — and probably radioactive materials — was penetrating the fence and pouring into the wider ocean. … TEPCO, based on the findings, concluded that a maximum of 10 trillion becquerels of radioactive strontium-90 and a further 20 trillion becquerels of cesium-137 may have reached the ocean.”

Tokyo, not Fukushima

But while the shadow of Fukushima hung over the vote, it has to be remembered that it was a vote on Tokyo – not Fukushima and not Japan. The Olympic Games are awarded to a city, not an area or a country, so the response from Tsunekazu Takeda, the head of Tokyo’s Olympic bid, made more sense: “Radiation levels in Tokyo are still the same as in London, New York and Paris.” Takeda told the media there was “nothing to worry about,” a statement that residents of Japan and the surrounding areas might not agree with. Takeda wasn’t lying. There was nothing to worry about at that moment, but there are worrying moments ahead, particularly from November when TEPCO starts to remove spent nuclear fuel rods from the damaged Fukushima power plant. It’s a very risky operation that has some activists painting a doomsday scenario not just for Japan, but for the whole world. This story isn’t over yet.

In reality, that’s another story. Having won the Games, Tokyo can now, hopefully, detach itself from the worries of Fukushima. Winning the Games is a cause for celebration, for both Japan and Tokyo. It’s been a long time coming.

Through the past darkly

Tokyo was initially awarded the Summer Olympic Games in 1940 but that was derailed by World War II. You might wonder what the International Olympic Committee was thinking awarding successive Games (1936 and 1940) to two belligerent, war-mongering states (Germany and Japan). Germany, despite being an economic and political basket case after World War I, was awarded the Games in 1931, just as Adolf Hitler and the Nazis were coming to power. The Nazis were already the second-largest political party in Germany and a year later they controlled the Reichstag. By the time Berlin hosted the Games, Hitler was chancellor of Germany and Nazism had spread its ugly shadow across the country.

Tokyo was awarded the Games in 1936, by which time it was already raping and pillaging its way across East Asia and had quit the League of Nations (the forerunner of the United Nations) the year before to facilitate its war-mongering ambitions. Yes, the IOC moves in mysterious ways.

Korean Sohn Kee-Chung won the 1936 Olympic marathon but had to run under the Japanese flag.

The IOC remembered Tokyo in 1959 – and curiously forgot all about the Pacific War – when it awarded the city the 1964 Games (Tokyo also bid for the 1960 Games, which went to Rome). While some might have wanted to punish Japan for its conduct pre-1945 – notably China and the two Koreas, who were still alienated from Japan politically – the 1964 Olympics served as a symbolic reintegration of Japan into the civilised world. And Japan responded with a dynamic, high-tech Games and a completely restructured city. Tokyo, in fact, dazzled the world in 1964. North Korea boycotted and Japan’s only hint of politicking came when the Olympic Flame was lit by runner Yoshinori Sakai who was born in Hiroshima the day the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on it.

Japan got another Olympics eight years later when Sapporo hosted the Winter Games, and they hosted the Winter Games again in 1998 in Nagano. With the 2020 Games, Japan will have hosted four Olympic Games, third overall and second-most – behind the United States – in the postwar era.

While the Winter Games carry a certain amount of prestige, Japan has been chasing the Summer Games for some time. Nagoya was stunned when it lost out to Seoul for the 1988 Olympic Games as the IOC once again opted to send the event to a country ruled by a murderous dictator (Chun Doo Hwan) just a year after he had slaughtered hundreds, maybe thousands, of civilians in the southern city of Kwangju. Of course, the selection of the host city has not always been untroubled by the exchange of favors and cash and Korea has some notable champions of bribery and corruption. A number of Olympic host cities have been accused of excessive “generosity” – including Nagano whose records were mysteriously burned when this topic came up. The IOC cleaned up its act by making changes to the bidding process, allowing its voters to concentrate on the merits of the bidding cities rather than the perks of their positions. Japan next put Osaka on the bidding list but it was doomed from the start after the IOC criticized the bid.

But 2016 was a different ball game. The Japan Olympic Committee decided to go with Tokyo rather than Fukuoka and Tokyo presented a beautiful bid for the Games. In fact, it earned the top rating from the IOC after the initial evaluation of the four bidding cities: Tokyo, Rio de Janeiro, Madrid and Chicago. Tokyo’s advantages were clearly superior to those of its rivals (although in truth any city getting to the final stages of a bid should be able to stage a decent Games). Tokyo claimed 2016 would see “the most compact and efficient Olympic Games ever.” But then the votes came in. Tokyo was third in the first two rounds of voting, meaning it was eliminated behind Rio and Madrid, which in turn was trumped by the allure of Rio de Janeiro and the attraction of seeing the Games in South America for the first time.

Live today, die tomorrow

So what changed for 2020? Bids from Rome, Baku and Doha were eliminated early on, leaving just three cities: Tokyo, Madrid and Istanbul. All three had been persistent triers. Madrid had actually won the first vote for 2016, beating Rio by two votes and Tokyo by six. All had attractions but suffered serious blows in the year before the vote. Madrid presented a very economical bid and was attractively placed globally; East Asia is often seen as an unreasonable time zone for broadcasts in the important couch-potato zones of Europe and the Americas, while Europe fits the bill perfectly timewise. Istanbul had the same momentum as Rio in that the Games could be held in a new area, a different (Muslim) culture and in a city that straddles Europe and Asia. Tokyo, meanwhile, had the money, the technology and the best layout for the Games. They all had something going for them.

But then the economic crisis really started to bite in Spain, which saw unemployment reach 25 percent. And some saw Madrid’s $2 billion budget – half that of Tokyo’s – as a sign of weakness. Olympic budgets invariable double, so there were also worries about whether or not Madrid would be able to keep up the payments with the national finances of Spain in such dire straits. Spain probably won on the affability stakes with Prince Felipe and Juan Antonio Samaranch Jr., the erudite son of the former head of the IOC. Despite its presentable facades, Madrid’s bid was seen to be built on weak foundations and it lost a runoff in the first round after tying on 26 votes with Istanbul; Tokyo got 40 votes.

Istanbul’s budget was a whopping $19 billion, which raised red flags all over the place. Imagine that doubling. Istanbul had the emotional momentum of Rio in that the IOC would like to spread its wings geographically and culturally, but the voters worried about its budget and the ability to deliver on infrastructure as everything would have to be new. That may not have proved fatal had the city not been hit by a wave of riots in the months leading up to the vote, not to mention the civil war in neighboring Syria.

Fukushima spread a cloud of doubt over Japan but unlike the crises in Spain and Turkey, the problem hadn’t directly affected the bidding city. The mere possibility of disaster/Armageddon trumped the ongoing problems in Turkey and Spain. Abe’s PR work really paid off. And so did Tokyo’s.

TEPCO’s Fukushima nuclear plant blows up

The 2016 bid was seen as spectacular from a technological point of view and drab from an emotional one. Bids need an emotional tone and faces that click with the IOC delegates. The presentations by then-Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama and then-Governor of Tokyo Shintaro Ishihara for the 2016 Games were limp at best. The message from Tokyo four years ago was effectively: We build good cars. Ishihara’s successor as governor, Naoki Inose, wasn’t a great improvement and made a couple of serious gaffes, but he didn’t carry Ishihara’s baggage. And, surprisingly, even Abe came over as a likeable chap in his presentation – made in much better English than Hatoyama’s.

And, as Abe shut the door on the horror of Fukushima, Paralympic athlete Mami Sato, also speaking in understandable English, opened the door to the emotions of the earthquake and tsunami, recounting how she didn’t know if her family in Miyagi were dead or alive for six days. Sato emphasized how Japanese athletes had embodied the Olympic spirit by countless visits to those affected by the disaster – and Tokyo’s bid had its emotional connection. As well as a good speech in English by Olympic fencing medallist Yuki Ota, Tokyo got two delightful speeches in French from HIH Princess Takamado and former news presenter Christel Takigawa.

Tokyo also moved out of Japan to spread the word overseas. It launched its candidature file in London rather than in Tokyo and in doing so was able to ride the coattails of a country that was still buzzing from its own wildly successful Olympics. It also campaigned strongly on the domestic front after the IOC had taken a dim view of support figures for 2016 that showed less than half of Tokyo’s population supporting a bid. Of course, half of 35 million is still rather a lot, but the perception was negative and had to be put right. One of the major plus points was the post-London Olympics parade of medallists through Ginza, which attracted half a million people – an astonishing number – and put the feel-good factor back into Tokyo. An IOC poll saw public support at 70 percent at the beginning of this year and a government poll saw that figure rise to 92 percent 10 days before the vote.

Living up to the past

So what does it mean for Tokyo and Japan?

From a sporting point of view, the Olympics represent the ultimate goal for many athletes. From an individual point of view, they aim for the Olympics and a home Olympics focuses that aim and intensifies the purpose. The host country usually increases the number of athletes and the number of medals. In 2008, for example, China fielded 639 athletes at the Beijing Olympics, earning 100 medals and 51 golds. Four years earlier, it had fielded 384 athletes, earning 63 medals and 32 golds. In 2012, Britain fielded 541 athletes for 65 medals and 29 golds, whereas in 2008, it had won 19 golds, 47 medals overall with 313 athletes.

The 1964 Games saw the city of Tokyo transformed. It was transforming itself anyway, but the Olympics provided the impetus to get things done and Tokyo placed priority on improving infrastructure that would assist the Games, including “road, harbour, waterworks development on a considerable scale over a significant area of the city and its environs.” Tokyo venues such as the National Stadium (soon to be rebuilt), Komazawa Sports Park and Yoyogi Gymnasium are still being used today.

Yoyogi Gymnasium, still in use today

If Tokyo wants to live up to its promises in 2020, it need look no further than 1964. Avery Brundage, the President of the IOC in 1964, was fulsome in his praise of Tokyo and the Japanese:

“No country has ever been so thoroughly converted to the Olympic movement. … Every operation had been rehearsed repeatedly until it moved smoothly, effortlessly and with precision. Every difficulty had been anticipated and the result was as near perfection as possible. Even the most callous journalists were impressed, to the extent that one veteran reporter named them the ‘Happy’ Games. This common interest served to submerge political, economic and social differences and to provide an objective shared by all the people of Japan. In Tokyo everyone united to clean, brighten and improve the city and a vast program of public works involving hundreds of millions of dollars was adopted. It remains a much more beautiful and efficient municipality with the handsome sport facilities erected for the Games as permanent civic assets. … The success of this enterprise provided a tremendous stimulus to the morale of the entire country. Japan has demonstrated its capacity to all the world through bringing this greatest of all international spectacles to Asia for the first time and staging it with such unsurpassed precision and distinction. It is certainly the Number One Olympic Nation today.”

As London showed in 2012, the Games can lift a whole country in many ways. According to a British government report published in July, the 2012 Olympic Games provided a £9.9 billion boost to the economy; saw 1.4 million more people playing sport at least once a week than in 2005 when the bid was won; brought £4 billion of investment into London; helped 70,000 workless Londoners into Games-related employment; and projected that the total benefit to the U.K. from hosting London 2012 could reach up to £41 billion by 2020.

Tokyo has just taken the first step. It has a lot of promises to live up to, but it also has a past to learn from. Perhaps it will lead to regeneration on a broader scale. As Olympic host and capital city, it has a responsibility to do things right.

What could possibly go wrong?

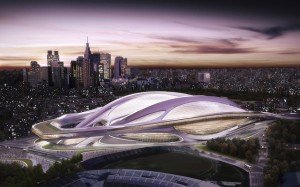

Graphic of how the 2020 Olympic Stadium will look