By Fred Varcoe

It happened again. I think it happens a lot. It shouldn’t be surprising, but it is.

About a year ago, I went to play Pacific Golf Management’s Chiba Kokusai Golf Club in Chiba Prefecture with my friend and regular golf buddy Don. Don had to leave by 13:30 in order to get to work on time. So we booked an early start time, around 7 a.m., figuring we could get through in less than six and a half hours. We also figured that as Chiba Kokusai has 45 holes, there wouldn’t be any great delays. We finished the first half at around 9:10 and, depressingly but not surprisingly, were told to take “lunch” and wait until 10:50 before we could play our second nine holes. Still, we figured we should be finished by 13:30. It shouldn’t take two hours and 40 minutes to play nine holes of golf on a 45-hole golf course.

It took an hour to play the first three holes, at which point we encountered a serious golf traffic jam. This sometimes happens at Par 3s but usually things clear up after that. That didn’t happen. If anything, the pace slowed. After finishing the seventh hole, it was nearly 13:30. “I’ve got to go,” Don said and he called the clubhouse to ask someone to pick him up along with his clubs. I figured I might as well get my money’s worth and finish the last two holes. But the man on the cart said “No!” I couldn’t continue as a solo player. Why? Who knows? There was no logical reason for denying me the last two holes. I was paying for 18 holes, I had a cart and I wasn’t holding any other players up. If I’d finished the last two holes, the second nine would have taken roughly three and a half hours. I thought that was scandalous and made my feelings felt with comments on the Golf Digest (GDO) website.

Amazingly, someone (from the golf club, I think) called me the next day to apologize. I suggested that, as Chiba Kokusai has three nine-hole courses plus a separate 18-hole course, they allow golfers to play through on the 18-hole course. I got some pro-forma apologies and nothing happened. Obviously, I haven’t been back to Chiba Kokusai again.

Fast forward to this year and Don and I are in the same situation. He has to finish by 13:30 to get to work, so we choose Moonlake Mobara (coincidentally and unfortunately another PGM course) as it’s close to home and has a 7:21 starting time. We finish the first nine by 9:10 and then, once again, are told to have “lunch” for an hour and 40 minutes. More traffic jams on the back nine but we finish at 13:30, so Don can get to work. That’s good, but why should a round of golf take six hours and why can’t we play through? Simple questions, but the answers aren’t simple.

The pointless lunch

Why do golf clubs in Japan – almost unique in the world – insist that you stop for lunch, even if “lunch” is at 9 o’clock in the morning? It’s part of a frustrating golf experience in Japan, which has a reputation for slow play, and an odd attitude to golf’s rules that edges toward stupidity at times.

A note on PGM’s parent company’s website gives the impression they want to change:

“In the future, while there is concern that players in their late 60s, who are the major golf players, will retire at a stretch, ‘one person reservation’ services such as increasing opportunities to visit golf courses are drawing attention. There is a movement to gain visitors. In addition, to make it easier for young people and women to participate, you can also find casual golf courses that can be enjoyed more casually, such as using nine holes instead of 18 holes per round, or shortening the time by through play.”

In other words: No halftime lunch. The compulsory stop for lunch is an obvious ploy to try and squeeze more money out of the golfer. Customers are prisoners of golf clubs. They can’t go anywhere, there aren’t any alternative eating establishments and they have nothing to do for an hour, so the clubs make them eat food, pay for the food and, hopefully, drink beer. In the past, this might have made some sense as a big lunch can cost quite a lot, especially if you include drinks and coffee. But this is now largely redundant. Most clubs now include lunch as a package, which means it’s not going to affect the cost of a round of golf. But it also means there is no reason to stop after nine holes as the golfer has to pay for lunch whether he eats it or not. And, of course, it doesn’t make any difference to the golf club if lunch is eaten after nine holes or 18 holes. If I start my round at 7:30 and it takes a “normal” four and a half hours to play 18 holes, I can then choose to go home at midday or eat lunch at lunchtime. More to the point, I won’t disrupt my rhythm on the course and my stomach won’t be weighed down with curry, rice and beer as I play my second nine.

One of the problems of the Japanese system is that it is so ingrained into the Japanese consciousness that golf clubs can’t even conceive of players playing through. On a number of occasions, I have almost had to force staff to allow us to play through. Once, after being told we couldn’t play through, we were waiting around and there was no one on the tee. Still, the reaction of the staff was NO. Eventually, they realised that there was a space on the schedule – which, of course, they hadn’t even checked – and reluctantly allowed us to go ahead and play half an hour earlier than our scheduled post-lunch tee time. Compare that to the club where I regularly play – Ichinomiya Country Club in Chiba Prefecture. The staff there – mainly old ladies – are just wonderful. They remember our names, they laugh and joke, they noticed when one player was absent for a long time (due to illness) and they know we always like to play through. The last time we played there, they said there was an opening after about 25 minutes. So, as usual, we sat down in the lobby for a quick drink. Moments later, one of the old ladies came rushing in looking for us and said they could squeeze us out if we could start immediately. This, Japan, is service. They always try to accommodate us and we know that if they can’t, it’s not for the lack of trying. Invariably, we start between 7:30 and 8 o’clock and finish by midday. Then we have lunch and everyone gets to work on time.

The irony of the Japanese system is that while the clubs might think they are earning more by forcing people to stop for lunch, they really aren’t. A golfer is far more likely to feel hungry at lunchtime rather than at 9 o’clock in the morning and is going to drink more beer after his round than during the round. But don’t try that now, especially if you start late. After finishing our round at Nouvel Golf Club in Chiba Prefecture, my friends and I went to the restaurant for some drinks and snacks. At 5:30, I went downstairs to take a shower. “No shower,” the manager said. “The bathroom is closed.” Ridiculous. That is not good service.

So, how does this compare with the West? Have Japanese golf clubs never heard of the 19th hole?

The 19th hole in the West is the bar/restaurant in the clubhouse, where people can drink and eat and chat and have a laugh. Many clubhouse bars and restaurants are open to the public and cater to groups, parties and even weddings. They are open all day and close late at night and are often a focal point in the local community. In effect, the catering side of the golf club is separate from the golf side but provides a greater service. OK, this isn’t going to work for many of Japan’s remote golf courses, but one of my local courses, Kimi-no-Mori, is on a housing estate that has very few catering outlets. An upmarket café/ restaurant has opened on the edge of the golf course and is doing terrific business but has no connection to the golf club. You would think that the golf club would have wanted to use its own extensive catering facilities for more than lunch. By doing so, it could play a greater role in the community and even attract more members. Ironically, a new restaurant has opened up around the corner from the clubhouse and is doing good business.

Slow, slow, slow

I was once playing golf in Los Angeles with a friend and I was keeping an eye on the group ahead of us. They’d started a hole or two in front of us but were getting slower and slower. I watched how they played, particularly on the greens. “They’re Japanese,” I said to my friend and when we caught them up, I was proved right.

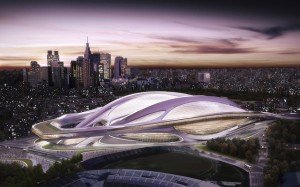

Lunch aside, why are Japanese golfers so slow? Well, it’s not all their fault. At a recent USGA-JGA symposium in Tokyo, most of the American speakers explained how they were trying to make golf a better all-round experience and create more customer satisfaction. They outlined the changes they were making and the targets they were aiming at. Most of the Japanese speakers had nothing to say, no results to explain and no vision of the future. They seemed reluctant to take on board the ideas expressed or else they just didn’t understand them. To their credit, Kasumigaseki Golf Club – the host club for the 2020 Olympic golf tournament – explained how they had done a heat-image survey of golfers on their course to find out where players went, where they didn’t go and where players got held up. Areas that players seldom visited needed less turf and less maintenance, so saving the course money, while logjams could be analyzed and solutions sought to maintain pace of play. Holes could be redesigned to be either more difficult or less difficult to adjust the pace of play. This might involve shifting a tee box back or forward or adding/ removing bunkers. Another way of improving pace of play was to lengthen the separation of tee times. The USGA reported that the biggest annoyance that golfers had on a golf course was being held up by other golfers.

The ritual of the green

Japanese golfers are so slow in putting, it’s painful to watch. In a casual round, me and my friends concede putts of around 50 cm or less. We just pick up the ball. Of course, in a competition you’re not going to do that, but in a friendly round, putting out is not really necessary, especially if there are people behind you. But the Japanese not only insist on putting out, they become obsessed with the ritual of the green.

They LOVE marking their ball, cleaning their ball, lining up a line on their ball and using their putters as a plumb line. And they love doing this on EVERY putt. Even if the putt is 20 cm. It wastes an inordinate amount of time and is largely unnecessary. I would guess that you don’t actually need to clean your ball more than 50% of the time. If the course is dry, dirt won’t stick to the ball. Japanese golfers think this is imperative, especially if you have a caddie to do it for you. There’s nothing quite like being a feudal master instructing your servants to do your bidding. This wastes time.

And the line on the ball? It’s there to help you square your club to the ball, but really I think it’s an illusion. It makes little or no difference to your putt unless you can line everything up perfectly, which most players can’t. And if you can, you probably don’t need a line on your ball. Yes, professionals do it, but they probably don’t need it either. The slightest deviance from your line’s alignment or the face of your putter renders the line useless. Even worse, it locks you into a shot when you need to retain some flexibility. When you address the ball from an upright position, the target will look different again. You might have to readjust. Not only will the line on your ball not help you, it will distract you from the target and the target is what you should be focused on. Mygolfspy.com did a comparison of putts of balls with a line and without a line and found that at 5 feet, there was a marginal advantage. But at longer distances (10 feet and 20 feet) the line on the ball was disadvantageous. The margin wasn’t huge, which seems to confirm that having a line makes no difference, so spending unnecessary time marking your ball and then annoying other golfers as you mistakenly align your line with your imagined route to the pin is just posing. Don’t waste my time!

Hurry up!

A recent marketing ploy by golf equipment manufacturers is the mini-bag, sometimes called a greenside bag. This is a little bag you can put your putter and wedges in and is another complete waste of time. My short-game set consists of my putter, 8-iron and three wedges. That’s all I’ll ever need and I can fit them in my hand quite easily. I don’t need to put them in another bag, unhook that and carry it to my ball. It’s another time-waster.

As is waiting for other people to play their shots after you’ve finished. It’s traditional for the player who is furthest away from the hole to go first, but this is not a strict rule. The actual rules state the following (bold emphasis is mine):

“A round of golf is meant to be played at a prompt pace.

Each player should recognize that his or her pace of play is likely to affect how long it will take other players to play their rounds, including both those in the player’s own group and those in following groups.

Players are encouraged to allow faster groups to play through.

(1) Pace of Play Recommendations. The player should play at a prompt pace throughout the round, including the time taken to:

Prepare for and make each stroke,

Move from one place to another between strokes, and

Move to the next teeing area after completing a hole.

A player should prepare in advance for the next stroke and be ready to play when it is his or her turn.

When it is the player’s turn to play:

It is recommended that the player make the stroke in no more than 40 seconds after he or she is (or should be) able to play without interference or distraction, and

The player should usually be able to play more quickly than that and is encouraged to do so.

(2) Playing Out of Turn to Help Pace of Play. Depending on the form of play, there are times when players may play out of turn to help the pace of play:

In match play, the players may agree that one of them will play out of turn to save time (see Rule 6.4a).

In stroke play, players may play “ready golf” in a safe and responsible way (see Rule 6.4b Exception).”

In other words, get on with the game.

But one sentence stands out from the above-quoted rules: “Players are encouraged to allow faster groups to play through.” This almost never happens in Japan for two simple reasons:

1. It’s barely a concept that’s thought about in Japan.

2. Fixed cart paths.

When I talked with Lauren Johnson, who gave a speech on pace of play at the USGA-JGA symposium, she wasn’t aware that the biggest obstacle to pace of play in Japan is that golf carts are invariably on a fixed path, making it impossible for one group to give way to another, faster group. Some courses do have free-roaming carts but they are expected to stay on the cart paths just like fixed carts. However, it is possible to play through and very, very rarely that happens. The old rules actually stated that two-ball groups had precedence over all other groups. In other words, you had to give way to a two-ball group. Now the rule is simpler, if the group behind you is faster, you should give way.

This almost never happens in Japan. But it’s not only other players who are to blame; the golf clubs and online booking services are also to blame. It’s very, very annoying when you book an early tee time for you and your friend only to find there’s one group ahead of you and it’s a foursome of old people who stick to their old traditions and think they’re playing by the rules. When you made your booking, there was no way of knowing who or how many people would be in front of you because online booking systems in Japan allow you to book two to four people on either the out course or the in course. Surely, there’s a more rational way of doing this. Wouldn’t it be better if all the foursomes were routed to one nine and all the twosomes to the other nine. Threesomes could go either way, hopefully ensuring that neither nine is overbooked. This would make it far more likely that the groups on one nine would progress at the same pace.

And then there’s the groups who want to play through. As I have stated above, clubs such as Ichinomiya will go out of their way to help groups play through, while others just don’t care or can’t be bothered. Why? Why? Why?

There really aren’t many reasons why playing through shouldn’t be an option at every golf course. The prime reason why golf clubs THINK they can’t accommodate golfers who want to play through is that they think it will be difficult. The real reason why I have to have nearly a two-hour lunch at 9 a.m. is because the tee times between 9 and 10:30 have already been allocated. Those starting early have to wait until all other groups that have booked have gone out. But the answer is very, very simple.

If a group that starts at 7 a.m. makes a booking with an option to play through, then the golf club eliminates a tee time at, say, 9:10 or 9:20 to allow that group to go through. They can add tee times after 10:30 to accommodate those who want to play a little later and still have the same number of groups each day finishing at the same time. There might be a need for all parties to be a little flexible, but players often have to wait anyway and traffic jams can cause heavy delays. Overall it would give players a more satisfying golf experience. Japanese golf clubs are wrong if they think that Japanese players don’t want to play through. It would also make sense for golf clubs to offer both earlier and later starting times to allow more groups on the course, especially at weekends. I once called a golf club from Narita airport asking for a tee time at 11 a.m. “We can’t do that,” came the reply. There were no starting times after 10:30. If the sun sets at 7 p.m., there should at least be starting times until 2 p.m. It’s very frustrating to drive past golf courses at 5 in the afternoon and see nobody playing, the flags removed and the course getting ready to shut up shop.

The last resort

Finally, there’s my experience at Kanucha Resort in Okinawa. I went there as a journalist and promised to publish my article on golf websites, a good opportunity for publicity for the resort. They came back with an offer: You can play six holes! If you think that sounds ridiculous, their next statement was even more absurd: “You can’t play on your own.” This is ridiculous in itself, but it is compounded by the fact that we’re talking about a resort golf course. So, a player could travel halfway around the world to experience an Okinawan golf course, he could take his clubs and his gear and then be told he can’t play because he’s on his own? At a resort course with almost no players on it? This is pure idiocy and symbolic of Japan’s resistance to change. In the West, a solo player expects to be teamed up with one, two or three other players, especially at a resort course or busy course. It’s nice to see there’s been a little headway on accommodating solo golfers in Japan, but so far the progress is slow.

And that is Japan: Progress is slow. When I worked at The Japan Times, my Japanese boss once refused to use an idea I had. I asked him why and he replied: “Because it’s never been done before.” Golf courses in Japan, which in general are a joy to play on, are facing a major crisis in the years to come as the population declines and the economy falters. If they’re not going to do stuff that hasn’t been done before, many of them are doomed.