RUNNING SENSIBLE

Would you leave?

Surely that should be “Running Scared”? Well, it was originally until some wiseguy in Tokyo actually used the phrase to describe my flight from my home.

Why wouldn’t I be scared?

A 9.0 earthquake, perhaps?

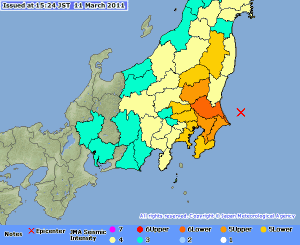

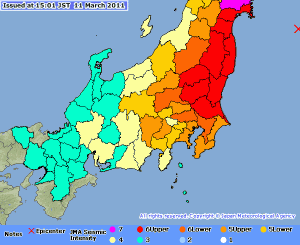

The 9.0 quake and how it shook Japan (see scale at the bottom). The epicenter is marked by an X in the top right corner.

Make that a 9.0 earthquake 400 km away. Only a few things fell down in my house; it didn’t do any damage. Physically. Twenty-five minutes after that quake, another one hit. It felt slightly stronger, but wasn’t so different. The second one was 7.9 on the Richter scale – but only 120 km away. In earthquake terms, that’s local. Scary enough for you?

That’s two huge quakes, but listen up: It wasn’t “The Big One.”

Tokyo got hit hard, but stood up to the quake pretty well. The northeast of the country has been pole-axed. There’s disruption everywhere, but not largely due to the earthquake itself. The BIG quake.

But the BIG quake wasn’t “The Big One.”

Tokyo’s last “Big One” occurred in 1923. The magnitude: 7.9, the same as the one that hit up the coast from me. It was at a depth of 23 km – not ultra-shallow, but not deep (the one near me was 39 km under the sea). Mainstream media almost never report the depth of an earthquake (although CNN’s meteorologists has been trying hard to improve, perhaps to compensate for their crap news reporting), but depth is crucial to what happens on the surface. The nature of the plate and fault line are also important. Some areas move more than others. And there are different kinds of motion.

The 1923 quake did not hit under Tokyo; it was in Sagami Bay, about 50 km away. But it was a long quake (an amazing 4-10 minutes according to Wikipedia), near the surface and produced a lot of ground movement. But it was not under Tokyo.

But both Tokyo and my house are close to major fault lines. The fault line that prompted the 9.0 quake on March 11 runs down the entire east coast of Japan, roughly from the northeast. Another fault line then cuts in from that about 75 km south of my house and juts into the bay south of Yokohama and Tokyo and then breaks south from Mt. Fuji. This fault line caused the 1923 quake and another large quake in 1703 (the Genroku Earthquake) that resulted in a massive tsunami in the area where I live (the Boso Peninsula) and, apparently, prompted an eruption from Mt. Fuji (still listed as an active volcano).

But the next “Big One” in Japan is supposed to be a Tokai quake that will hit the Shizuoka area roughly 150 km southwest of Tokyo. Experts tell us it’s on the way, based on previous earthquake cycles. Of course, in the meantime, we’ve had a number of large and deadly quakes, including Kobe in 1995 (a mere 6.8 on the Richter scale, but at only 16 km depth – 6,500 dead; Niigata 2005 (6.9 on the Richter scale, also at 16 km depth – 39 dead); Niigata 2007 (6.6 at 10 km – 11 dead). The Tokai quake is expected to be 8-8.5 on the Richter scale in an area where the plate is near the surface. Estimate deaths: 10,000 (that will only be revised upward after the recent quake). A big Tokyo earthquake or a Tokai earthquake will cause more disruption and damage (at least from the quake) than the recent 9.0 quake. Judging by what’s happened in the last few weeks, it will be devastating to Japan’s economy. The human cost will also be horrendous.

According to The Japan Times of March 20, 2003:

“A Tokai quake centered on central or western Shizuoka Prefecture or Suruga Bay would force the evacuation of some 2 million people and disrupt the water, electricity and other infrastructure of 5 million others, the panel said. … A massive Tokai quake could also trigger tsunami of up to 10 meters striking coastal regions stretching from the Boso Peninsula in Chiba Prefecture to Mie and Wakayama prefectures on the Kii Peninsula.”

Tokyo’s last big earthquake was in 1923, 88 years ago. Before that, came the Ansei-Edo quakes in 1854-55. That’s quakes. Not one, but three over a period of less than two years. There’s always more out there. Yes, I’m scared.

TSUNAMI

And then there are tsunamis. We live 100 meters from the sea at an elevation of roughly 5 meters. I have had unsettling dreams about tsunami since I moved here. I know the danger. I know we have to get out and away from the sea when a quake hits. I’d always had a plan in mind. Assuming that I could get out in my car and the roads weren’t blocked, I figured I could get to my friend Mike’s clifftop house in a couple of minutes. Plan B (if the roads are blocked, a likely scenario) is to walk up the little road in front of my neighbour’s house and climb the hill above it (the sea’s on the other side). I can’t quite figure out how high the mountain is. I’ve always based my escape plan on the basis that a 10-meter wave would be heading our way. This is very possible.

My next-door neighbour reminds me that the Tohoku quake and tsunami was a “once in a thousand years event.” Not quite true. The media have reported it that way, but the truth is that it was a “once in a thousand years event” in that location. There’s a lot of locations… I live at a different location; the clock is still ticking.

The urgency I have about evacuating is the result of knowing about another earthquake and tsunami that happened in Japan in 1993, and which, curiously, has been largely forgotten, even now. A 7.8 earthquake struck off Okushiri Island in northern Japan on July 12, 1993 (more information here: www.drgeorgepc.com/Tsunami1993JAPANOkushiri.html).

Waves of at least 10 meters (and up to 20 meters) hit the island within two minutes at its nearest point. Villages were wiped out. But not everyone was killed. Although 269 people lost their lives, another destructive earthquake 10 years earlier (no “once-in-a-thousand-years” event here) taught people that they had to run to higher ground very, very fast. I’m hoping the hill near my house is high enough for refuge, but I don’t know how high it is, or even if I can get to the top with a wife and 3-year-old child. It could be pitch black and in the summer there are poisonous snakes and other wildlife in the hills. And what if the waves were 40 meters high. Apparently, it’s happened before. Of course, if I thought it would happen to me, I wouldn’t have bought a house so close to the sea. You run a risk. There might not be another major quake in this area for 500-600 years. There might be one tomorrow.

FALLOUT

Three days after the March 11 quake, a friend called me. He had spoken to a couple of credible nuclear engineers. They advised him to get out of town. He advised me to escape immediately. Others were urging caution. A number of friends reminded me that no official spokespeople could be trusted, least of all the buffoons at TEPCO. The government couldn’t afford to have 30 million people in the Tokyo area panicking.

I had this vague belief that my toxic lifestyle over the years would grant me immunity from any poisons heading my way, but that wouldn’t apply to my daughter, who was a week away from her third birthday. Cancers start easily in children hit by radioactivity. But there were other reasons why getting away would be good.

For a start, aftershocks. I actually had some work to do when I got back to Japan on March 10. In fact, I had a lot of things to catch up on. There were around 150 recorded aftershocks on March 12; that’s around six an hour. They just kept coming. I would sit at my desk, the cabinet would rattle and I’d be out the door like a shot. And not just six times an hour. There were aftershocks that shook my house that didn’t make the earthquake list. Just little jolts. Little jolts that would wake me up and get my heartbeat racing. I couldn’t concentrate in such conditions.

We had only transferred our bedroom to an upstairs room a few months ago. The upstairs shakes easily and the bedroom was not designed for a quick exit. So, after returning home on March 12 (we slept at the local golf club on March 11), we slept downstairs near the front door with the entrance light on and the door unlocked, keys and passports at the ready. Sleep was fitful at best. And what was it doing to my daughter. If there was a significant aftershock, we’d bundle her up and head for the front door.

“Jishin? Jishin?” she would ask, practising her latest Japanese word. When she looked at the news on the TV, she would say the same. “Jishin? Jishin?” I was worried her nerves were as frazzled as mine and my wife’s.

Gas for cars was already being rationed, electricity cuts were on their way, you couldn’t buy milk and some foodstuffs and there were predictions of large aftershocks and serious pollution from the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station.

Geez, what would be the sensible thing to do in these circumstances? Ah! That’s it! Stay at home and take it like a man, and tell my wife and child to stop whining. Living in fear would toughen them up!

Or I could go to a place where there were no earthquakes, no power cuts, plenty of gas, milk, water, food, life.

On March 15, we headed to Shimizu in Shizuoka Prefecture to stay in a hotel for four nights. After that, a friend lent me his family’s mountain house near Umegashima hot-spring resort – very remote, very peaceful, fucking cold and famous for landslides. And right in the region where the Tokai Earthquake could occur, I foolishly reminded myself.

But lightning doesn’t strike twice, does it?

We celebrated our escape that evening in a Korean restaurant. The beer tasted good. We could relax. As I drank my cold beer, the ground started shaking and shaking as a 6+ earthquake (on the Japanese scale; 6.2 on the Richter scale) shook Mt. Fuji, 50 km away.